by Kaitlin Schlotfelt, Family Programs Manager

From the NCSML for Women’s Month:

Free First Saturday for Students / Czech Your Car / March 3, 9:30 a.m. – 4:00 p.m.

For Women’s Month we will be making our own toy race cars in honor of the first woman to win a Grand Prix event — Elizabeth Junek, a Czechoslovakian automobile racer in the early 1900s. Cost: Free for students, regular admission for non-students.

Kären Mason, curator of the Iowa Women’s Archives (at the University of Iowa Libraries) will talk about the significance of 6-on-6, drawing on personal narratives from Iowa Women’s Archives collections. Cost: free to attend.

Every year the National Women’s History Project picks a theme for Women’s Month – which is March – and this year they have chosen Nevertheless She Persisted: Honoring Women Who Fight All Forms of Discrimination Against Women. “Through this theme we celebrate women fighting not only against sexism, but also against the many intersecting forms of discrimination faced by American women”

Every year the National Women’s History Project picks a theme for Women’s Month – which is March – and this year they have chosen Nevertheless She Persisted: Honoring Women Who Fight All Forms of Discrimination Against Women. “Through this theme we celebrate women fighting not only against sexism, but also against the many intersecting forms of discrimination faced by American women”

With March marching around the corner we’re looking to honor women in history with two programs – Free First Saturdays for Students (March 3) and our first History on Tap for 2018 (March 14) – both focusing on stories about women and their accomplishments.

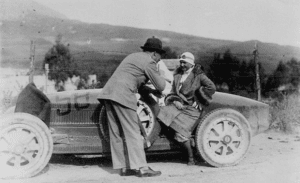

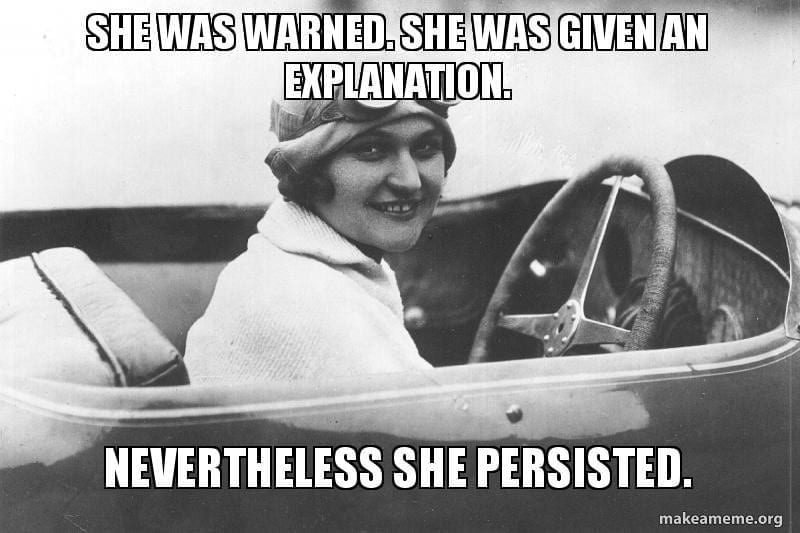

For Free First Saturday for Students this month we will be making little cars in honor of Eliška “Elizabeth” Junek. Junek was a Czechoslovakian driver in the early days of racing when it was dangerous to simply drive, let alone in a competition. She is recognized as one of the greatest female drivers in motor racing history, given the name “Queen of the Steering Wheel.”

For Free First Saturday for Students this month we will be making little cars in honor of Eliška “Elizabeth” Junek. Junek was a Czechoslovakian driver in the early days of racing when it was dangerous to simply drive, let alone in a competition. She is recognized as one of the greatest female drivers in motor racing history, given the name “Queen of the Steering Wheel.”

She was born in the Moravian area of the Czech lands in 1900 – at this time they were still part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. By the age of 16 she knew several languages including English and German, which allowed her to get a job in a bank. That was where she met her future husband Vincenc “Čeněk” Junek, who got Eliška into automobiles. “If he is going to be the love of my life, then I better learn to love these damned engines,” she said.

Eliška learned how to drive and received her license in secret while Čeněk began his solo racing career. Once he won the Zbraslav-Jiloviste race in 1922, they were married and began their joint racing career. During World War I Čeněk had been shot in the hand, which eventually made it difficult for him to shift gears. This paved the way for Eliška to switch from solely being the riding mechanic to the driver as well. A year later she made her solo debut and right out of the gate she began making a name for herself. A mere three years after her husband won the Zbraslav-Jiloviste race, she took the prize herself.

Eliška learned how to drive and received her license in secret while Čeněk began his solo racing career. Once he won the Zbraslav-Jiloviste race in 1922, they were married and began their joint racing career. During World War I Čeněk had been shot in the hand, which eventually made it difficult for him to shift gears. This paved the way for Eliška to switch from solely being the riding mechanic to the driver as well. A year later she made her solo debut and right out of the gate she began making a name for herself. A mere three years after her husband won the Zbraslav-Jiloviste race, she took the prize herself.

While the Junek power couple were leading in the races, both together and individually, they were also the darlings of society. They were the “it couple” and seen as role models – especially in Czechoslovakia. In 1928, Eliška almost took first place at the Targa Florio! She was in the lead, or second, for several laps – ahead of such folks as Luigi Fagioli, René Dreyfus, Ernesto Maserati, and Tazio Nuvolari – before she got a flat tire in the final lap, finishing in fifth place.

If you watch a lot of TV shows or movies, you know when things are going too well at this point in the story, clearly some tragedy is around the bend. Later that year, at the 1928 German Grand Prix, they were sharing the drive. Čeněk had just moved to the driver’s seat when they crashed. He was killed and Eliška retired soon after out of grief.

The Juneks had a great relationship with the Bugatti family – yep, the ones with the world-renowned cars. Eliška’s signature car on the road was actually a Bugatti Type 30. When Eliška left the racing world she sold off all of the couple’s cars and went travelling. To aid in her journeys, the Bugattis gave her a car and employed her as an agent in other countries.

At the beginning of her racing career she was seen as a “small girl” and told that she “didn’t have the muscle” to compete with her male peers. However, she went on to not only show that she was competent, but that she was talented. She left her mark in racing history, from being the first person to walk the course before the drive – a practice still done today – to being the first woman to win a grand prix.

Czech out this YouTube interview with her about Targa Florio 1928.